Management Styles in Horror: What Zombie Apocalypses and Alien Invasions Teach Us About Leadership

Horror films and series aren’t usually considered management textbooks. But survival scenarios reveal leadership in its rawest form—when stakes are highest, resources are scarce, and every decision matters. Let’s examine what some of horror’s most iconic survival stories reveal about different management approaches, and why some leadership styles get everyone killed while others keep teams alive.

The Transformational Leader: Rick Grimes (The Walking Dead)

Rick Grimes starts as a small-town sheriff who wakes up to a world that no longer follows any rules he knew. His evolution from hesitant leader to someone his group would follow anywhere represents transformational leadership at its most extreme.

What makes it work

Rick doesn’t just tell people what to do—he demonstrates. When Alexandria’s residents don’t understand the new reality, he doesn’t lecture them. He gets his hands dirty, shows them how to survive, and proves his methods work. This is leadership by example taken to its logical extreme: if you’re not willing to do it yourself, you can’t ask others to do it.

He also makes the hard calls. Not the dramatic, self-serving hard calls that bad managers hide behind to justify cruelty, but the genuinely difficult decisions that keep people alive. When he realizes the old rules don’t apply anymore, he adapts. When his approach stops working, he changes it.

Where it gets complicated

Transformational leadership demands enormous personal investment. Rick carries the weight of every decision, every loss, every moral compromise. This approach works brilliantly in crisis mode but becomes unsustainable long-term. Even fictional characters break under this pressure—and real managers definitely do.

The danger lies in becoming so focused on survival that you lose sight of what you’re surviving for. Rick occasionally crosses this line, making choices that keep everyone breathing but damage their humanity. It’s the eternal management dilemma: achieving goals versus maintaining values.

The real-world parallel

Every startup founder in crisis mode, every manager navigating a company restructuring, every team leader dealing with impossible deadlines—they recognize this style. It works when you genuinely need someone to carry the team through chaos. It fails when leaders mistake every situation for a crisis or forget that people need more than just survival.

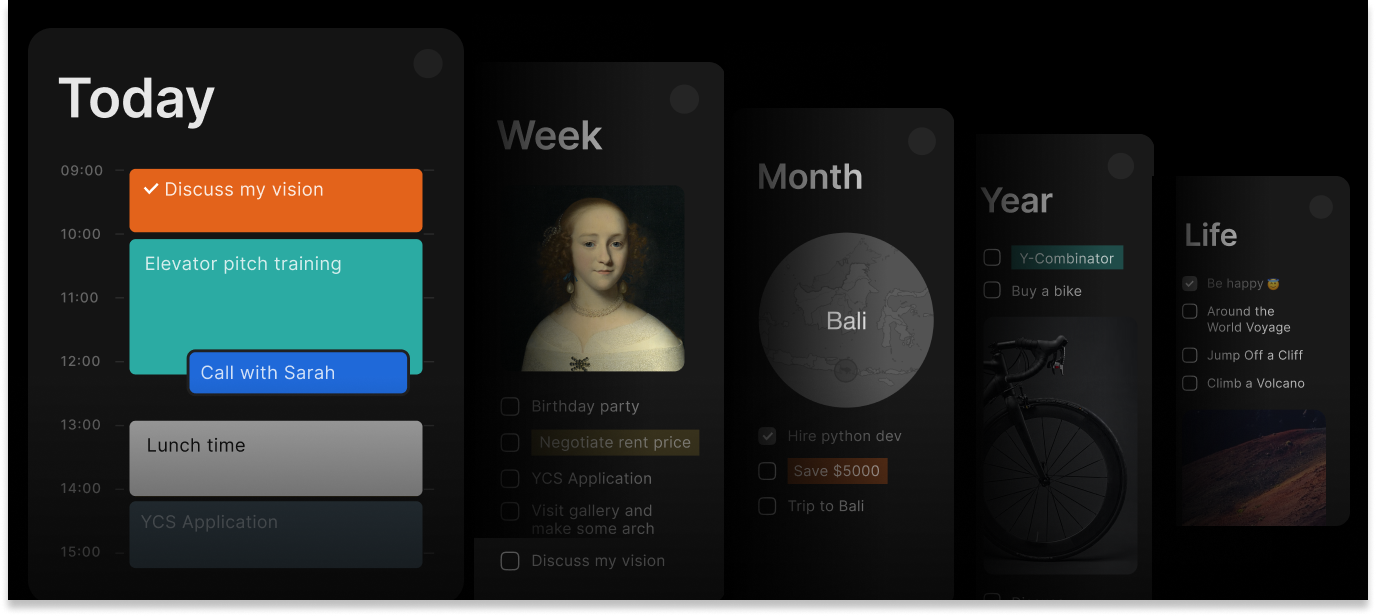

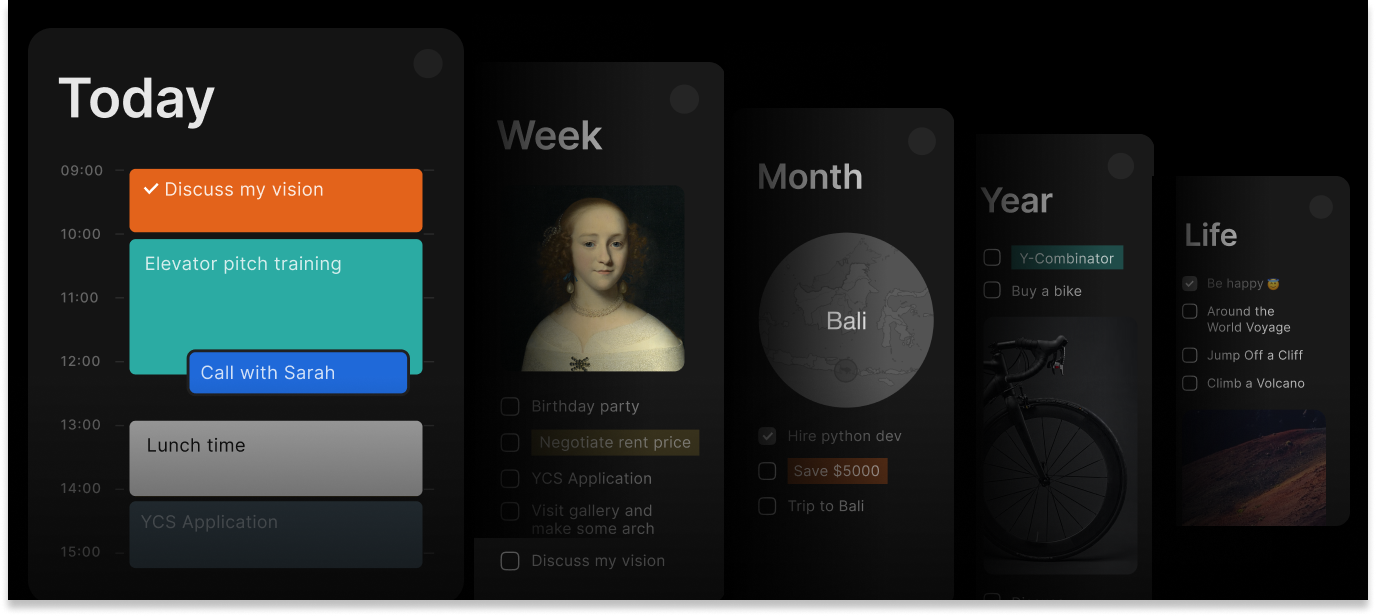

Want to organize your team’s survival strategy?

Check out Timestripe’s planning features

Get StartedThe Protocol-Driven Manager: Ellen Ripley (Alien)

Ripley starts as Warrant Officer on the Nostromo, third in command, following protocol to the letter. When Kane returns from the alien planet with something attached to his face, Ripley refuses to let him back on the ship. Not because she’s cruel, but because quarantine protocol exists for exactly this reason.

Her captain overrides her. The alien gets on board. Everyone dies except Ripley.

What makes it work

Protocols exist because someone, somewhere, learned something the hard way. Ripley understands this instinctively. She respects procedures not because she lacks imagination, but because she understands they encode lessons from previous disasters.

When protocol fails—when the company’s true priorities become clear, when the android proves unreliable, when all the rules stop mattering—Ripley adapts. She shifts from following protocol to improvising solutions, but her foundation in systematic thinking gives her an edge. She doesn’t panic and flail; she assesses, plans, executes.

Where it gets complicated

Rigid adherence to protocol in the face of completely novel situations can be fatal. Ripley’s strength lies in knowing when rules apply and when they don’t. Many protocol-driven managers never develop this flexibility. They cite policy when creative solutions are needed, hide behind procedures when leadership demands courage.

The deeper issue: protocols can’t cover every situation. Someone eventually needs to make judgment calls. Ripley does this brilliantly in later films, combining her systematic approach with hard-won experience and genuine care for her team.

The real-world parallel

Every quality assurance professional, every compliance officer, every operations manager who’s ever been overruled by someone focused solely on speed recognizes Ripley’s position. Following established procedures often looks like being obstructionist or uncreative. Right up until something goes catastrophically wrong and everyone asks why protocols weren’t followed.

Good protocol-driven management isn’t about blind rule-following. It’s about understanding why rules exist, knowing when they apply, and having the authority to enforce them when necessary.

The Silent Coordination Master: The Abbott Family (A Quiet Place)

In a world where sound means death, the Abbott family operates as a perfectly synchronized unit. Lee and Evelyn don’t have the luxury of verbal instructions, team meetings, or written memos. Every member of the family knows their role, understands the stakes, and executes flawlessly through silent coordination.

What makes it work

This family demonstrates something most managers struggle to achieve: complete operational clarity without constant communication. Everyone knows what needs to happen, why it matters, and how their actions affect others. They’ve established systems—painted floorboards to show safe paths, sand trails to walk silently, light signals for emergencies.

The protocols aren’t bureaucratic overhead. They’re survival mechanisms that everyone helped develop and genuinely understands. When Lee teaches his son to fish silently or Evelyn prepares the soundproof birth room, they’re not just following orders. They’re executing a shared strategy that everyone’s invested in.

Trust forms the foundation. Lee and Evelyn don’t micromanage. They’ve trained their children thoroughly, established clear systems, and then trust them to execute. When Marcus needs to handle something alone, he can—because he’s been genuinely prepared, not just told what to do.

Where it gets complicated

This level of coordination requires extensive upfront investment. The Abbotts spent years developing their systems, training each family member, and building the infrastructure that keeps them alive. Most organizations want results immediately without investing in the foundation.

There’s also limited room for innovation or questioning. When survival depends on exact execution of established procedures, creative problem-solving becomes dangerous. The systems work brilliantly—until they encounter a situation they weren’t designed for, like Evelyn going into labor alone.

The real-world parallel

High-performing teams in high-stakes environments operate this way. Surgical teams, emergency responders, elite military units—they achieve seamless coordination through extensive training, clear protocols, and deep trust. Everyone knows their role so well that they can adapt without detailed instructions.

The mistake many managers make is trying to achieve this coordination without the investment. They want teams that “just know what to do” but haven’t put in the work to build systems, establish clarity, or develop trust. They want the Abbott family’s execution without the Abbott family’s preparation.

The other mistake is maintaining this approach when the situation changes. The family’s systems work perfectly for their established threats but struggle with new challenges. The best teams know when to execute the playbook and when to throw it out.

The Paranoia Generator: The Research Team (The Thing)

MacReady and the Antarctic research team face something unprecedented: a threat that looks exactly like them. The Thing can perfectly imitate any team member, which transforms normal workplace dynamics into lethal paranoia. What starts as a functional research team descends into complete distrust.

What makes it fail

This isn’t really about MacReady’s leadership—it’s about what happens when trust completely evaporates. When you can’t be certain who’s actually on your team, every interaction becomes suspect. People stop sharing information because they don’t know who might use it against them. Collaboration becomes impossible because you can’t trust your collaborators.

The real killer isn’t the alien. It’s the breakdown of social cohesion. The team had the resources, skills, and intelligence to handle the situation. What they couldn’t handle was operating in an environment of total mutual suspicion. Palmer might be Palmer. He might be the Thing. You can’t build a team when you can’t trust anyone.

MacReady tries to maintain control through testing and verification, essentially creating a trust-through-proof system. But this only works to a point. You can verify someone’s identity at a specific moment, but the paranoia remains. The damage to team dynamics persists even after the immediate threat is addressed.

Where it gets complicated

Some level of healthy skepticism in organizations is good. Blind trust creates vulnerability. But there’s a spectrum between naive trust and paranoid suspicion, and The Thing shows what happens at the extreme end.

When teams operate in high-suspicion environments—whether from actual threats or toxic culture—productivity collapses. People spend more energy on self-protection than actual work. Information hoarding becomes survival strategy. Collaboration feels dangerous.

The tragic irony is that the suspicion itself becomes the weapon. Even if only one or two team members are actually threats, the paranoia affects everyone. The Thing doesn’t need to assimilate the entire team. It just needs to destroy their ability to work together.

The real-world parallel

We’ve all seen teams implode not from external threats but from internal suspicion. Maybe there’s an upcoming layoff and everyone suspects everyone else of politicking for survival. Maybe there’s a leak to management and now nobody knows who to trust. Maybe the performance review system pits people against each other for limited rewards.

The pattern is the same: legitimate cooperation becomes impossible when trust evaporates. People start optimizing for self-preservation rather than team success. Information stops flowing. Collaboration stops happening. The team might still exist on paper, but it’s functionally dead.

The management lesson isn’t about fighting alien parasites. It’s about recognizing that trust is infrastructure, not a nice-to-have. When that infrastructure breaks down—through poor management, toxic incentives, or actual bad actors—rebuilding it requires more than just identifying and removing threats. You need to actively reconstruct the conditions that make trust possible.

Some managers create Thing-like environments deliberately, believing competition and suspicion drive performance. They’re right that it drives something. Just not usually the outcomes they want.

What Horror Teaches Us About Management

Here’s what these four very different scenarios reveal: leadership isn’t about finding the one correct management style. It’s about understanding what different situations demand and having the flexibility to adapt.

- Rick’s transformational approach works when you need someone to carry the team through crisis and inspire them to become more than they thought possible. But it’s exhausting and unsustainable as a permanent state.

- Ripley’s protocol-driven method prevents disasters and provides structure. But protocols need wisdom about when to follow them and when to adapt.

- The Abbott family’s silent coordination demonstrates what’s possible when you invest in systems, training, and trust. But it requires that upfront investment and the wisdom to know when your systems need updating.

- The Thing’s research team shows what happens when trust infrastructure collapses. It’s a cautionary tale about both external threats and the internal dynamics that make teams functional or dysfunctional.

The managers who survive horror scenarios (literal or metaphorical) are the ones who genuinely care about their team’s survival, who adapt their approach to circumstances, who make hard choices but don’t hide behind them, who build and maintain the trust that makes everything else possible.

The ones who get everyone killed? They’re usually the ones who prioritize their own authority over the team’s survival, who stick rigidly to one approach regardless of context, who mistake cruelty for strength or indecisiveness for thoughtfulness, who create environments of suspicion and fear.

In Practice

You probably won’t face a zombie apocalypse, alien invasion, sound-hunting monsters, or shapeshifting parasites. But you’ll definitely face situations where resources are scarce, stakes feel impossibly high, trust becomes critical, and your leadership choices materially affect people’s lives.

In those moments, the question isn’t “which management style is correct?” The question is: “What does this specific situation demand, what are my team’s actual needs right now, what trust infrastructure exists or needs building, and am I willing to adapt my approach accordingly?”

Horror teaches us that leadership isn’t about having one perfect style. It’s about having the awareness to recognize what the situation requires, the flexibility to adjust your approach, the wisdom to build and maintain trust, and the courage to make decisions when others can’t or won’t.

Also, maybe listen when someone says we should follow quarantine protocol. Ripley was right.

And definitely invest in training your team before the crisis hits. The Abbotts were right too.

And please, for the love of everything, don’t create workplace cultures where people suspect their colleagues might be alien parasites. MacReady would probably agree with that one.

Read next